Observing the secretive inhabitants of the Monticello, Utah, Disposal Site.

March 3, 2021Landscapes at U.S. Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management (LM) sites are as variable as they are numerous, providing habitat for a wide variety of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. Some LM sites are even home (or are potentially home) to wildlife species afforded special federal, state, or tribal protections because their populations were deemed at-risk due to low numbers.

Why does wildlife matter at LM sites? For one, LM supports the beneficial reuse of its lands by conserving natural resources and conducting activities that are environmentally sound. Conservation reuse activities such as ecological revitalization of a site can encourage recreational activities and economic development. LM sites don’t exist in isolation — they are a piece of a larger ecological puzzle. A vital component of this puzzle is the animals that rely on these sites for food, water, refuge, finding mates, or rearing young. As such, natural resources (including plants and animals) may need to be assessed for a number of reasons, including determination of a site’s potential for conservation reuse, as part of a baseline characterization during the transfer of a site to LM, or to determine if a protected species occupies or could occupy the site.

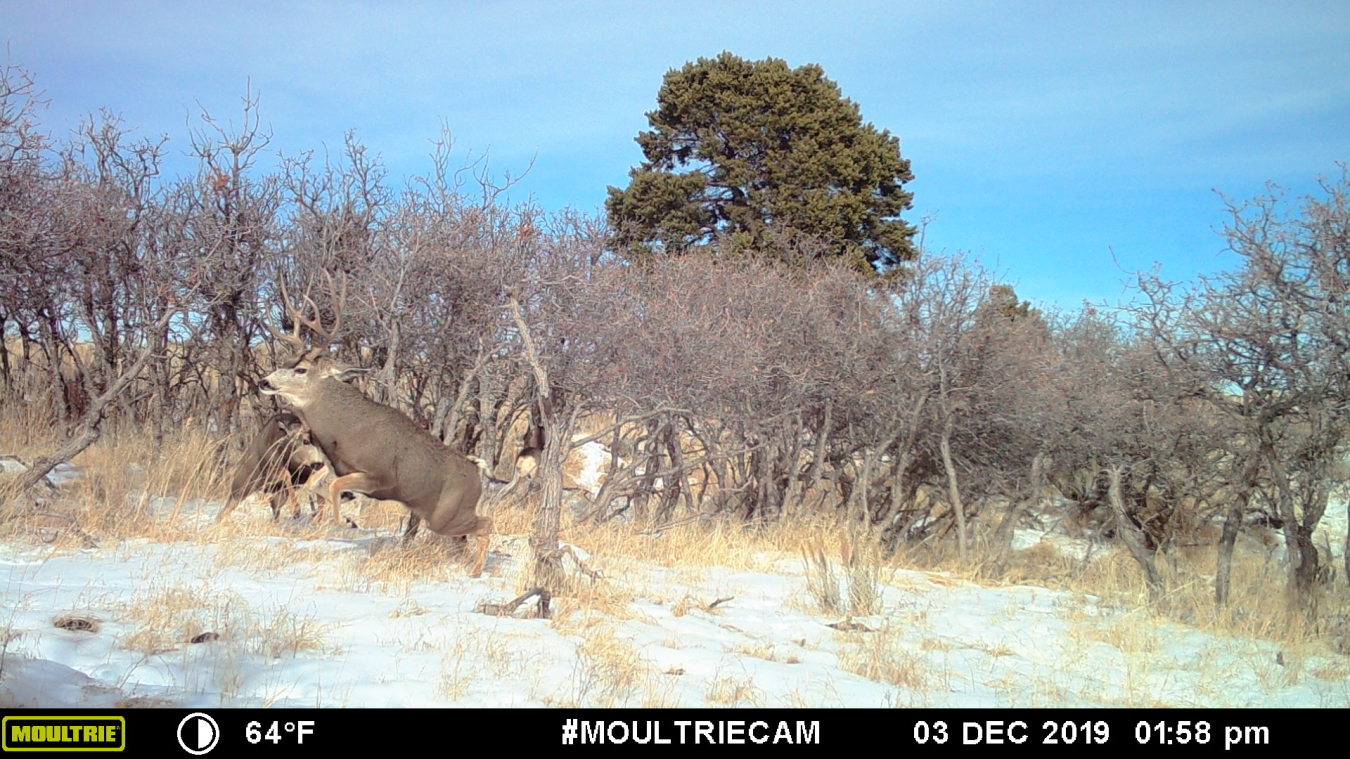

Two mule deer bucks fighting during the rut.

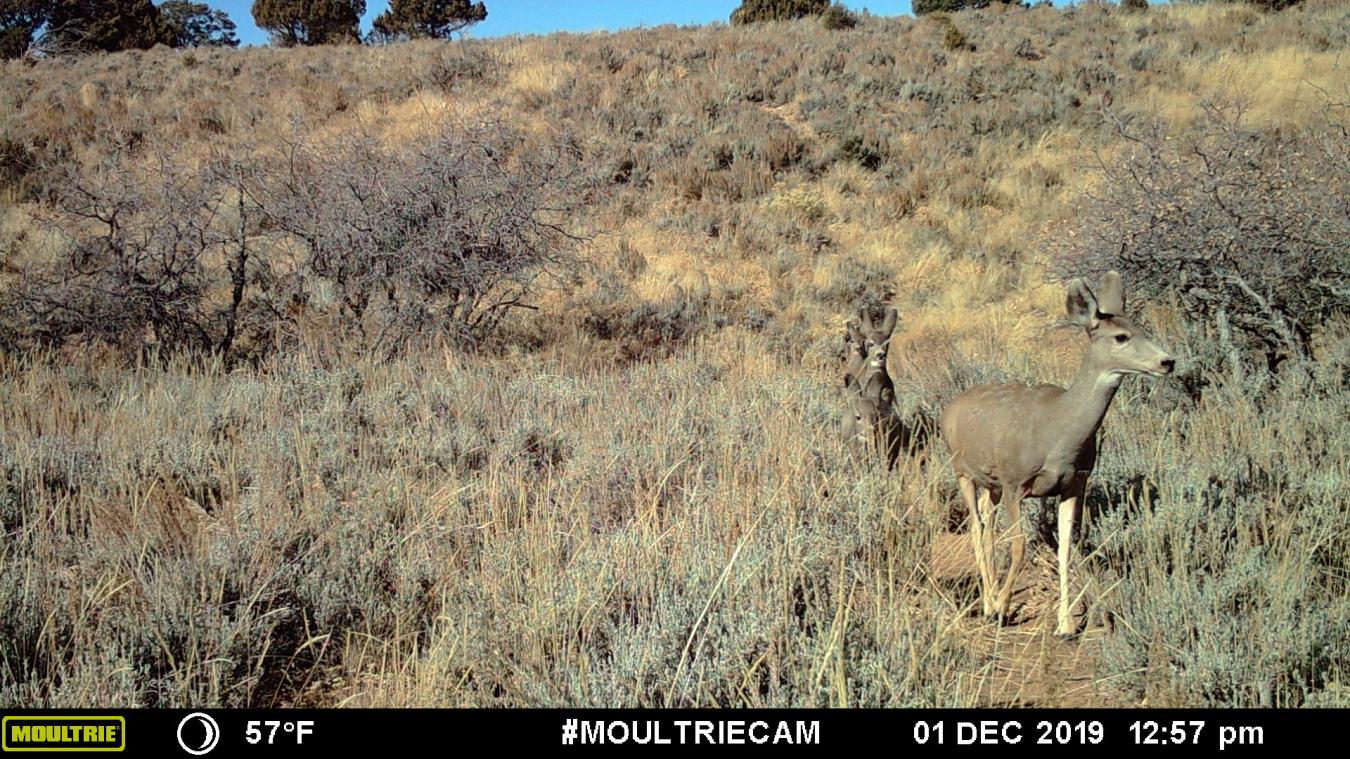

A mule deer doe leading three fawns through the sagebrush.

How does LM assess these natural resources? In the case of plants, it’s straightforward — ecologists conduct a systematic visual survey of the site. This is highly effective because plants can’t run or fly, they typically don’t hide, and they surely can’t migrate when times get tough. Wildlife, on the other hand, may scatter without much warning. This can make boots-on-the-ground visual surveys less effective — a phenomenon known as “imperfect detection” in biostatistician parlance.

Remotely placed, motion-activated cameras (also known as game or trail cameras) have become increasingly popular among wildlife biologists for documenting wildlife and their activities. These small, relatively cheap, customizable, weather-resistant cameras can operate continuously for months without maintenance, providing unprecedented insight into the lives of wildlife. Consider the advantages of this technology: day or night, rain or shine, hot or cold, full moon or new, windy or calm, these cameras continue making observations, without substantially disturbing or otherwise altering an animal’s behavior.

How can trail cameras benefit LM? To answer this question, four trail cameras were deployed at the Monticello, Utah, Disposal Site, with two primary goals: to monitor for presence of the Gunnison sage-grouse, a bird protected as threatened under the Endangered Species Act; and to document overall biodiversity at the site. Though not previously observed, the site exists within the sage-grouse’s potential range, as designated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Over a 1-year period, the cameras were strategically located and periodically moved across the site to maximize the possibility of “capturing” wildlife, especially in the spring when male sage-grouse perform elaborate strutting displays and vocalizations to attract females to their breeding grounds (called leks), thus increasing the probability of observing this species if it was present (even transiently).

A wild turkey passing through the site.

Mule deer sparring.

Joyce Chavez, the LM Reuse Asset manager, was pleased with the results. “I am so excited to see all of the wildlife activity on the site, as so many of our LM sites in the western United States are ideal for promoting native ecology,” she said.

From October 2019 to October 2020, thousands of pictures of wildlife were captured, including 11 mammal, eight bird, one lizard, and one grasshopper species. Wildlife included mule deer, elk, fox, coyote, northern harrier (hawk), wild turkey, black-tailed jackrabbit, mountain cottontail, striped skunk, numerous rodents, and even a hummingbird. No sage-grouse were documented.

Perhaps more notable were the behaviors of the animals captured: mule deer sparring, elk foraging, a hawk patrolling the grasslands. One thing was evident: animals were not just passing through the site — they were using it.

Many species were recorded repeatedly throughout the year, but mule deer were most frequently seen. From rutting (breeding season activities) in the winter to fawning in the spring, seasonal routines were readily on display. This is a promising observation because mule deer have experienced population declines in parts of the West, prompting state and provincial fish and wildlife agency personnel to collectively work together to address long-term declines of this species.

What did we learn?

Trail cameras are an effective, low-cost tool that can be used to passively survey wildlife presence and activity at LM sites. An unanticipated finding of this project was the variability in sizes of animals detected by the cameras, which ranged from adult elk to grasshoppers. The ability to document something as small as a grasshopper expands the potential application of this technology to detect or monitor smaller animals, such as important pollinator species. While these cameras cannot completely replace traditional ground surveys, they are a useful supplement that can allow LM to better understand how sites are functioning as part of the larger ecological puzzle.

A northern harrier patrolling the site.

An elk grazing at night.