Learn more about FECM’s work with critical minerals in this Q&A with Grant Bromhal, Senior Science Advisor in FECM’s Office of Resource Sustainability and Acting Division Director of Mineral Sustainability.

Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management

April 30, 2024The U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management’s (FECM) Critical Minerals Sustainability Program is working to ensure a domestic supply of critical minerals by accelerating production from unconventional and secondary sources. Learn more about FECM’s work with critical minerals in this Q&A with Grant Bromhal, Senior Science Advisor in FECM’s Office of Resource Sustainability and Acting Division Director of Mineral Sustainability.

When we look at the elements of the periodic table, we see that nearly half the minerals in existence are listed as “critical” to U.S. supply chains and mostly imported for overseas. How is FECM addressing this issue?

The first message is that this is a big challenge that will require big solutions that are not all “one-size-fits-all.” We will have to do what we can to rise to the challenge. US is currently dependent on foreign sources for the critical minerals and rare earth elements we need for batteries, wind farms, solar panels, the grid and more.

The second message is that the entire periodic table can be found in coal, so coal-based feedstocks can provide many of those critical minerals.

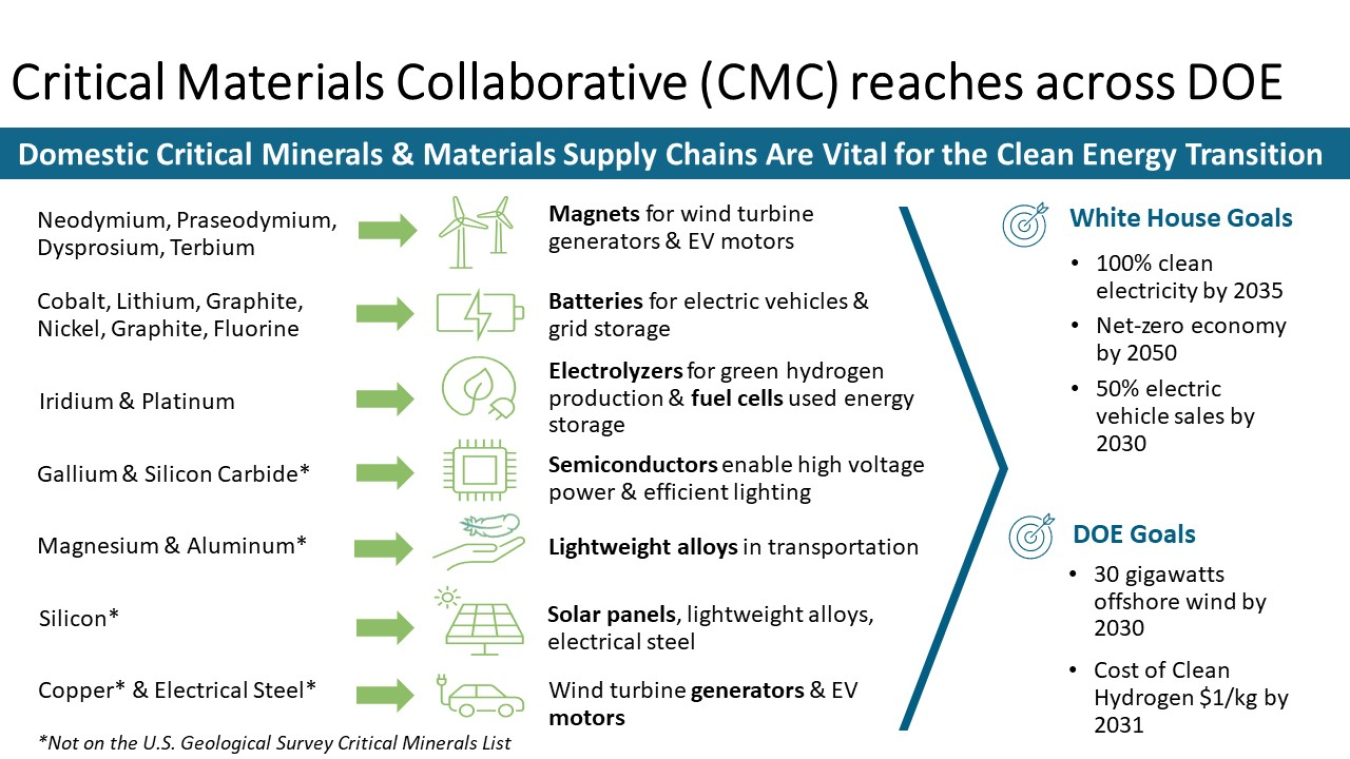

But half the periodic table is not much of a focus, so what DOE has done is create critical mineral assessments that have allowed us to narrow our focus around the energy-relevant critical minerals and material supply chains.

Is there a way to see how critical a particular mineral or material is for U.S. national interests?

By looking at the material criticality of each mineral for use by the United States, DOE has sharpened its focus to a smaller set of critical materials that are the most important for energy production and the clean energy transition.

This chart shows the most critical materials with the highest supply risk in the short and medium term (upper right corner of the graphs). These materials include the rare earth element dysprosium -- used in magnet manufacturing – as well as lithium and nickel. Also high on the list of minerals with high supply risk are cobalt, graphite, magnesium and other rare earths like gallium, terbium, and iridium.

What are the primary areas that DOE is focusing on in terms of minerals needed for the clean energy transition?

The first area of focus is battery supply chains, which everyone expects to grow enormously and will include powering electric vehicles and energy storage, which in turn helps both the grid and transportation systems.

The second area of focus is magnets. There are critical amounts of rare earth elements, such as terbium and dysprosium, within electric vehicles and wind turbines, and powerful magnets are in almost everything we use for national defense.

After that, you see critical minerals needed to manufacture electrolyzers that catalyze green hydrogen and make fuel cells.

Nearly all the most important minerals – not just rare earth elements but also graphite, cobalt, nickel and platinum – are found not just in mines, but also in coal gob piles and coal ash impoundments around the country.

These minerals exist in lower concentrations than in a mine. Still, the point is these valuable materials are already dug up and next to these existing mines or abandoned mining sites. Additionally, current mining for minerals typically only focuses efforts on producing the primary mineral from a mine, when in reality, there may be a number of potential co-product and by-product minerals found in the same rock. Why not use what has already been pulled out of the ground?

There is very little critical minerals refining in the United States today. How far do you think the nation can get in terms of domestic refining in the next several years to decades with the help of these DOE demonstration projects?

DOE estimates that the United States uses 30,000 tons of mixed rare earth oxides each year. In 2023, funding for the first rare earth element demonstration facility was allocated, and it is expected that this first-of-a-kind facility will be finished by 2028. One demonstration plant supplies three percent of current domestic demand – a significant piece of the pie for a single demonstration plant. There is no magic number of plants needed, but the domestic market for mixed rare earth oxides will be over 200,000 tons annually in the next 20 years.

Not all rare earth elements are created equal. Lighter rare earth elements are more abundant than heavy rare earth elements.

The only existing rare earth mine in the United States is Mountain Pass in California, which produces 16 percent of the world’s rare earth elements, but has shipped what it has produced to China for processing.

While the Mountain Pass mine produces very little heavy rare earth elements, rare earths produced from coals are relatively enriched with heavy rare earths. This means the potential supply for heavy rare earths can be found in coal slag heaps around the United States, which is more significant than within many rare earth mines.

Nation-wide, wastes and byproducts from known fossil fuel reserves and other industries currently contain more than 10 million tons of rare earth elements, which is equivalent to more than a 300-year supply at the current rate of U.S. consumption.

________

Are you the next FECM #AllStar?

FECM is looking for enthusiastic, driven professionals to join our team and be a part of the clean energy revolution. We are seeking highly skilled individuals who are passionate about helping FECM achieve its mission, which is focused on minimizing the environmental impacts of fossil fuels and industrial processes while working toward net-zero emissions. View our current job openings and workforce development programs.

Learn More

To learn more about how FECM is supporting the development of a domestic supply of critical minerals, sign up to receive email updates and follow us on X, Facebook, and LinkedIn.