The United States leads the world in geothermal electricity-generating capacity—just over 4 gigawatts. That’s enough to power the equivalent of about 3 million U.S. homes.

To generate power from geothermal systems, three elements are needed:

- Heat—Abundant heat found in rocks deep underground, varying by depth, geology, and geographic location.

- Fluid—Sufficient fluid to carry heat from the rocks to the earth’s surface.

- Permeability—Small pathways that facilitate fluid movement through the hot rocks.

The presence of hot rocks, fluid, and permeability underground creates natural geothermal systems. Small underground pathways, such as fractures, conduct fluids through the hot rocks. In geothermal electricity generation, this fluid can be drawn as energy in the form of heat through wells to the earth’s surface. Once it has reached the surface, this fluid is used to drive turbines that produce electricity.

Conventional hydrothermal resources naturally contain all three elements. Sometimes, though, these conditions do not exist naturally—for instance, the rocks are hot, but they lack permeability or sufficient fluid flow. Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) use humanmade reservoirs to create the proper conditions for electricity generation by injecting fluid into the hot rocks. This creates new fractures and opens existing ones to enhance the size and connectivity of fluid pathways. Once this engineered reservoir is created, fluid can be injected into the subsurface and then drawn up through a production well to generate electricity using the same processes as a conventional hydrothermal system.

The 2019 GeoVision analysis concluded that, with advancements in EGS, geothermal could power more than 40 million U.S. homes by 2050 and provide heating and cooling solutions nationwide. The 2023 Enhanced Geothermal Shot™ analysis found that the potential was even higher: technical advances would enable geothermal energy to power the equivalent of more than 65 million U.S. homes

GTO is also assessing opportunities to use sedimentary geothermal resources to produce electricity. Sedimentary rock formations commonly associated with oil and gas can also hold significant amounts of thermal energy. This creates opportunities to access additional geothermal resources and even to repurpose idle or unproductive oil and gas wells for geothermal electricity generation.

Geothermal Power Plants

Geothermal power plants draw fluids from underground reservoirs to the surface to produce heated material. This steam or hot liquid then drives turbines that generate electricity before it is reinjected back into the reservoir.

There are three main types of geothermal power plant technologies: dry steam, flash steam, and binary cycle. The type of conversion is part of the power plant design and generally depends on the state of the subsurface fluid (steam or water) and its temperature.

See how we can generate renewable energy from hot water sources deep beneath Earth's surface. The video highlights the basic principles at work in geothermal energy production and illustrates three different ways Earth's heat can be converted into electricity.

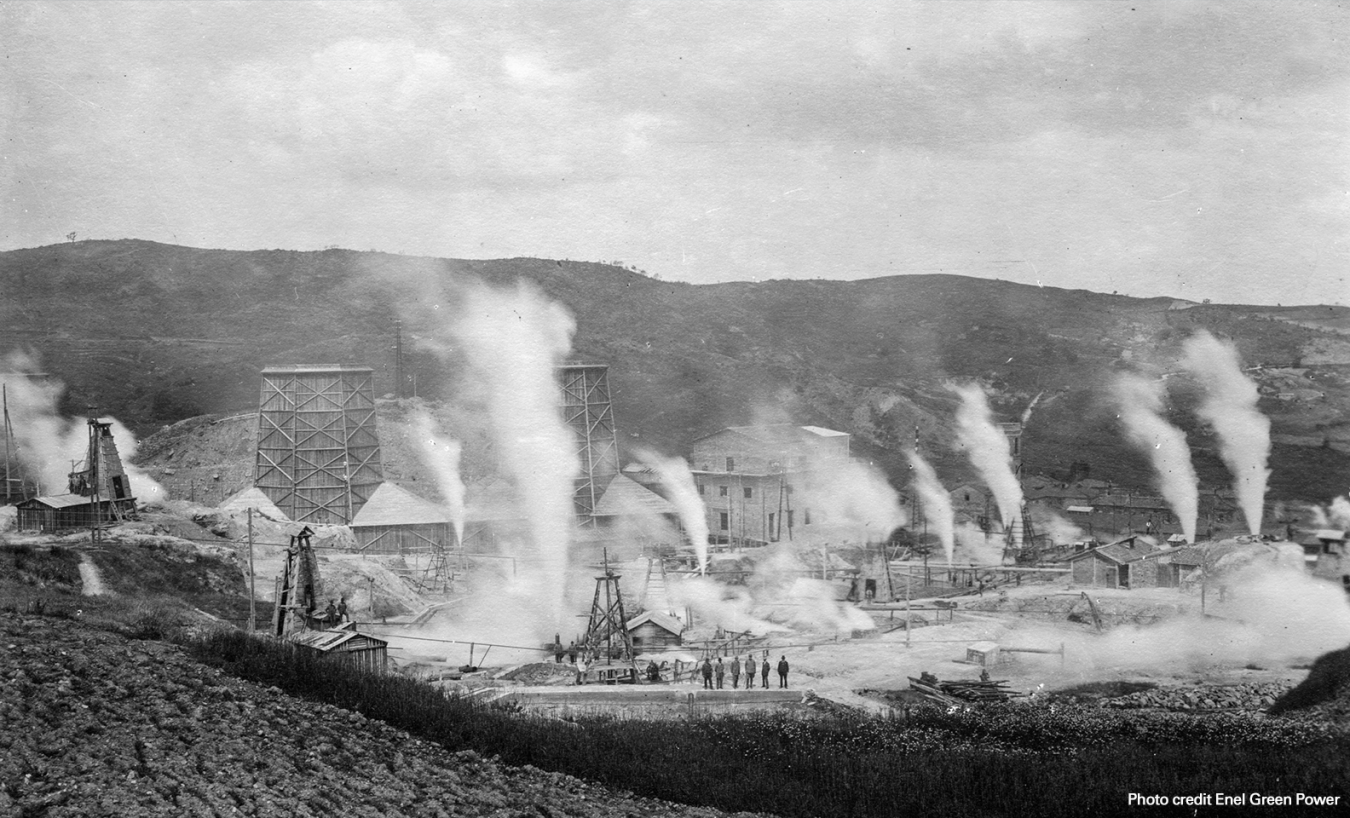

Dry Steam Power Plant

Dry steam plants use hydrothermal fluids that are already mostly steam, which is a relatively rare natural occurrence. The steam is drawn directly to a turbine, which drives a generator that produces electricity. After the steam condenses, it is frequently reinjected into the reservoir.

The Larderello geothermal power plant in Tuscany is the oldest dry steam power plant in the world.

Dry steam power plant systems are the oldest type of geothermal power plants, first used in Italy, in 1904. Steam technology is still relevant today and is currently in use in northern California at The Geysers, the world's largest single source of geothermal power.

Flash Steam Power Plant

Flash steam plants are a common type of geothermal power plant in operation today. Fluids at temperatures greater than 182°C/360°F, pumped from deep underground, travel under high pressures to a low-pressure tank at the earth’s surface. The change in pressure causes some of the fluid to rapidly transform, or “flash,” into vapor. The vapor then drives a turbine, which drives a generator. If any liquid remains in the low-pressure tank, it can be “flashed” again in a second tank to extract even more energy.

Binary-Cycle Power Plant

Binary-cycle geothermal power plants can use lower temperature geothermal resources, making them an important technology for deploying geothermal electricity production in more locations. Binary-cycle geothermal power plants differ from dry steam and flash steam systems in that the geothermal reservoir fluids never come into contact with the power plant’s turbine units. Low-temperature (below 182°C/360°F) geothermal fluids pass through a heat exchanger with a secondary, or "binary," fluid. This binary fluid has a much lower boiling point than water, and the modest heat from the geothermal fluid causes it to flash to vapor, which then drives the turbines, spins the generators, and creates electricity.

GTO emails bring geothermal funding opportunities, events, publications, and activities directly to your inbox.