Gary DeBoer is Making It! This former AAAS fellow urges us to make decisions that will better the lives of future generations.

Advanced Materials & Manufacturing Technologies Office

August 20, 2024As a kid, Gary DeBoer could scamper out his back door and skip through lake-sized corn fields whose dancing stalks led him straight to his cousins and pick-up games of baseball, tag, or capture the flag. DeBoer grew up in Iowa on the belt buckle of the Corn Belt, a Midwest region where cornfields reign. There, he was surrounded by his extended family of Dutch farmers (“de boer” means “the farmers” in Dutch), and he loved everything about it.

But one day, his dad, who worked for the local farmers’ co-op, came home with a furrowed brow.

“We could only sell 5 gallons of gas to each farmer today,” DeBoer overhead his dad tell his mom. The Arab oil embargo of 1973 and 1974 had just started, and farmers were starting to feel its pinch.

With only a fraction of the oil, farm equipment could only do a fraction of the job, and production lagged. Young Gary could sense the mounting stress. “That’s when I started thinking, ‘Well, what if I could build a machine that worked without gas?’” DeBoer said. “All the tractors could run on some electrified batteries or something.”

Making It!

AMMTO’s Making It! series spotlights the fresh perspectives of our fantastic fellows, who are making next-generation materials and manufacturing processes possible for our clean energy future.

Of course, in the 1970s, such technology only existed in science fiction or short-lived factories. But today, electric vehicles and renewable energy not only exist; they’re also the future of our clean energy economy. And today, DeBoer—who is a professor of chemistry at LeTourneau University and recently served as an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology fellow with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)—gets to help make his dream the new norm.

“It took 50 years for it to happen,” DeBoer said. “But as a kid, this is what I wanted to do: save the world with respect to energy. And I got to be part of that at DOE.”

Up until Aug. 9, 2024, DeBoer worked with DOE’s Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Technologies Office (AMMTO), which focuses on improving energy storage and battery manufacturing. If our country could manufacture novel battery technologies on its own soil, that would give Americans the energy independence we didn’t have during the 1970s oil crisis.

“If we can develop that new skill, we can have some control over our destiny with respect to energy, batteries, electric vehicles or grid storage, renewable energies, and all those other things,” DeBoer said. “So, I’ve got to save the world, basically.”

In this Q&A interview, DeBoer shares why he left his beloved Iowa farmland behind, his experience as a first-generation college student, and why he sees batteries as key to saving the world. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

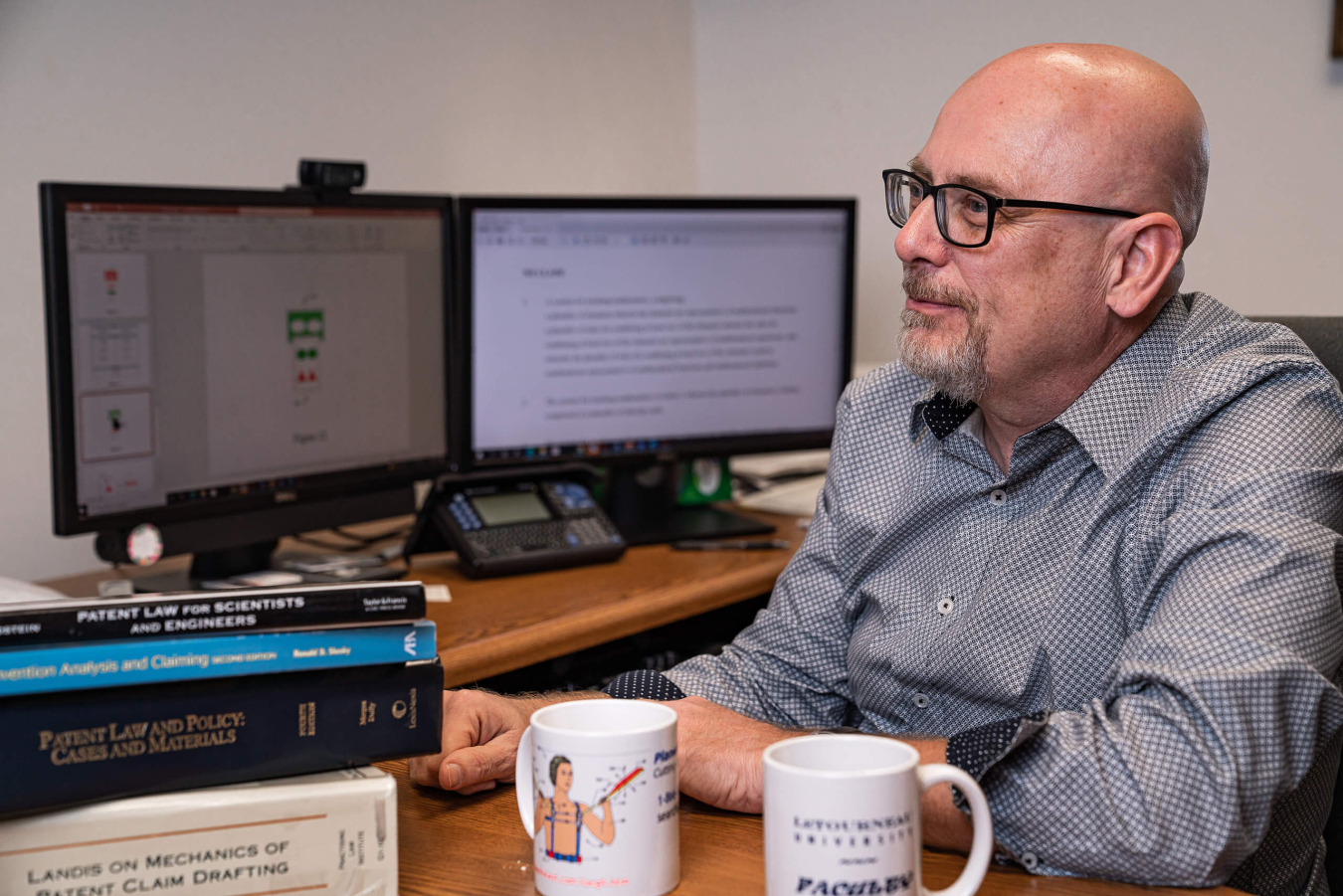

When a young Gary DeBoer witnessed Iowa farmers, including his family, struggle through the Arab Oil Embargo, he aspired to build farm equipment that didn’t depend on oil. Today, he aspires to create a country that no longer depends on oil. Photo from LeTourneau University

Did you have a specific career in mind when you were a kid?

I wanted to be a lawyer or a scientist because I thought lawyers looked cool wearing suits and carrying briefcases into courtrooms. And scientists always looked good with lab coats and all their cool chemistry equipment. Now, in science policy, like what I’m doing at DOE, I’m kind of doing both legal and science work. So, I think I’ve achieved it all now. Everything else is going to be anticlimactic.

So, it sounds like your younger self wouldn’t be surprised to see where you ended up.

Well, yes and no. My younger self would say, “I would love to be that, but also, we’re just farmers. We don’t go to college.”

What does your family think about the path you took?

Most of the time, they don’t really talk to me much about the work I do. We’ll talk about the flooding in Iowa and how the corn is not going to come up. But I think my parents are reasonably proud of me.

What was your career path like? Did you go straight from college to get your higher degrees?

No, no. I took a long, long circular route to things. In college, all my roommates were brilliant physics and robotic engineering majors. I thought, “I could never keep up with guys like that in graduate school. I’m just lucky to graduate from college.” So, I said, “Well, I can do something they can’t do,” and I joined the Peace Corps.

Wow! Where were you stationed?

I went to the Pacific [Republic of Kiribati] and had a really good time. Because the U.S. Marines saved the Pacific Islanders from the Japanese in World War II, there were still a lot of good vibes for Americans. When I came back from the Peace Corps, I was getting married, and I thought I should get a “real job.” So, I worked as a chemist making electrochromic mirrors for cars—automatically dimming mirrors that maybe your parents had in their cars—at Gentex Corporation in Michigan.

How did you decide to go back to school?

Gary, pictured here with his wife, said his time at DOE was a kind of pinnacle of his career. “It’s exciting to go from being that small child who saw the turmoil of the Arab oil embargo and now seeing we can be energy independent on renewable energies that aren’t going to poison our lakes and ponds, increase global temperatures, cause sea level rise, and all the rest,” he said. Photo from Gary DeBoer

After a while in industry, it was like, “This is all cool, and I've learned a lot, but it's not answering the big questions. It’s not the ‘save the world’ thing.” So, I went to graduate school at the University of Iowa because I’m from Iowa. That was close to my parents, so they could see their granddaughter grow up. But after I graduated, I took a job teaching at LeTourneau University in Texas, where I work now. We just got tired of Iowa’s cold weather.

Why did you choose to study physical chemistry for your Ph.D.?

When I was working in industry, I was doing a lot of organic synthesis, making electrochromic materials that went into the mirrors. And organic chemistry—that stuff is really smelly. So, I took the purest, idealistic antithesis to organic chemistry, which is physical chemistry. I did spectroscopy, quantum mechanics, and all that stuff to keep myself away from smelly solvents.

Did you face any obstacles along your career path?

Not really. I’m a white Dutch guy from the Midwest, right? The biggest challenge I had was that my parents had no personal experience to advise me as a college student. But fortunately, my roommates’ parents were doctors and lawyers and such, so I listened in on their conversations on how to make smart choices. If I had different roommates, who knows what I would have done.

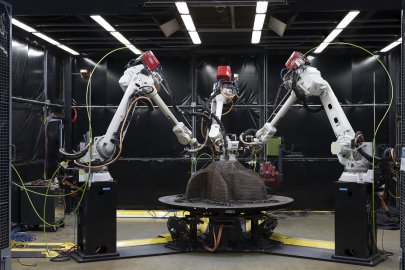

What excites you most about the work you did with AMMTO? What problems were you trying to solve?

I worked in AMMTO’s energy storage subgroup, which is mostly focused on batteries. Batteries are full of advanced materials, especially new batteries, and it’s very difficult to manufacture them. We don't do much of that in the United States. At AMMTO, I was engaged with several funding opportunity announcements and lab calls to advance battery technology. We’re hoping to start new manufacturing in the United States, leap ahead of others, and become independent, energy wise. I was also part of a working group on advanced manufacturing in low Earth orbit, which was great for someone who remembers the Apollo missions.

What do you mean by “energy independent”?

When some people say we need to be energy independent, they’re talking about “drill, baby, drill.” I’m thinking, “Manufacture, baby, manufacture.” Drilling is not always going to be there. By manufacturing our own energy storage devices with our own renewable energy resources, we’ll be truly off the global oil grid.

Most of the world’s big problems come down to overpopulation and a lack of resources, like energy. We have to bring resources to the people without causing further harm. DOE is really the department of everything that’s going to save the world.

It’s not a matter of the technology; it’s a matter of us deciding to pursue and implement the technology. It’s up to us to make decisions that will better the lives of future generations.

In an ideal world, what would you most hope to accomplish?

Today, Texas ranchers worry about their cattle because they’re in the heat more and they use more energy to cool themselves, which means they put on less weight. In Iowa, farmers are seeing severe weather—long periods of drought and big rainfalls and flooding.

My grandparents were farmers, my dad was a farmer, and I still have a bit of farmer in me as well. Most of my cousins were farmers and many still are. They expect that their grandchildren will be farmers there one day. But how?

It’s not a matter of the technology; it’s a matter of us deciding to pursue and implement the technology. It’s up to us to make decisions that will better the lives of future generations. I don’t want to say, “Sorry, granddaughter. I made a bad decision. You weren’t born yet, but I thought I was right.” I want to say, “This was a turning point in history, and the world came together to invest in smart technologies that didn't cause further damage.” I want to be able to say, “I was part of that solution.”

What advice would you give to folks who also want to be part of that solution?

Get a good chemistry and physics education. Take all the math courses. If you want to work in the STEM fields somewhere, you’ve got to have some math. There are other things you can do in the sciences—become a patent lawyer or a science writer—but it helps to have general knowledge of what science is about.

And take advantage of fellowships and other programs that DOE has to offer! Because if you’re like me and you grew up in Iowa and didn't know anybody anywhere in college, you can make connections with those labs and that will get you on track.

Relevant News

-

For as long as she can remember, Emilie Lozier has found comfort in science. Now, she applies that same scientific curiosity to tackling energy technology and workforce challenges for a cleaner, greener future.

For as long as she can remember, Emilie Lozier has found comfort in science. Now, she applies that same scientific curiosity to tackling energy technology and workforce challenges for a cleaner, greener future. -

DOE‘s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research Program is accepting applications for Implementation Grants. AMMTO is especially interested in funding research in pursuit of the circular economy, smart manufacturing and energy-efficient microelectronics.

DOE‘s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research Program is accepting applications for Implementation Grants. AMMTO is especially interested in funding research in pursuit of the circular economy, smart manufacturing and energy-efficient microelectronics. -

Happy belated Nanotechnology Day! Nanotechnology is the manipulation and manufacturing of materials and devices on the scale of atoms or small groups of atoms.

Happy belated Nanotechnology Day! Nanotechnology is the manipulation and manufacturing of materials and devices on the scale of atoms or small groups of atoms. -

DOE’s Lab-Embedded Entrepreneurship Program (LEEP), managed by AMMTO, welcomed its 2024 cohort to its headquarters in Washington, D.C. to kick off their two-year fellowships

DOE’s Lab-Embedded Entrepreneurship Program (LEEP), managed by AMMTO, welcomed its 2024 cohort to its headquarters in Washington, D.C. to kick off their two-year fellowships -

Look out for a funding opportunity from the AMMTO-sponsored High-Performance Computing for Manufacturing program. Coming later this fall!

Look out for a funding opportunity from the AMMTO-sponsored High-Performance Computing for Manufacturing program. Coming later this fall! -

Jon-Edward Stokes is Making It! In a Q&A interview, how his shifted his academic focus from English to science and what gives his career purpose.

Jon-Edward Stokes is Making It! In a Q&A interview, how his shifted his academic focus from English to science and what gives his career purpose. -

Check out the winning projects funded by AMMTO. Congratulations to the winners!

Check out the winning projects funded by AMMTO. Congratulations to the winners! -

DOE announced funding for three additional projects focusing on various materials and manufacturing technologies for offshore wind.

DOE announced funding for three additional projects focusing on various materials and manufacturing technologies for offshore wind. -

Gary DeBoer is Making It! This former AAAS fellow urges us to make decisions that will better the lives of future generations.

Gary DeBoer is Making It! This former AAAS fellow urges us to make decisions that will better the lives of future generations. -

A $33 million funding opportunity aims to accelerate the advancement of smart manufacturing technologies and processes necessary to develop and deploy the innovative technologies and materials needed for the nation’s clean energy transition.

Get the latest Making It! profile and other advanced materials and manufacturing news in your inbox.