Former worker reflects on Chicago facility where history was made

December 22, 2023

The most unassuming places can hold historical significance of immeasurable weight.

The Chicago South, Illinois, Site is located near Ellis Avenue and 58th Street, on the University of Chicago campus. The 171-acre location today might seem like just another site at first glance, but it housed events that would shape history.

Well before the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management took long-term stewardship responsibilities for it, the site at the University of Chicago was used for scientific research under the code name “Metallurgical Laboratory,” developing technology critical to the goals of the Manhattan Project.

The Manhattan Project involved research and development during World War II to create the first nuclear weapons, bringing the world into the Atomic Age. The Allies were racing against the clock to develop a nuclear weapon before their Axis counterparts. The Chicago South site was a key location in that endeavor, operating between 1942 and 1951. It was on the site in December 1942 that scientists initiated the first self-sustaining, controlled nuclear chain reaction.

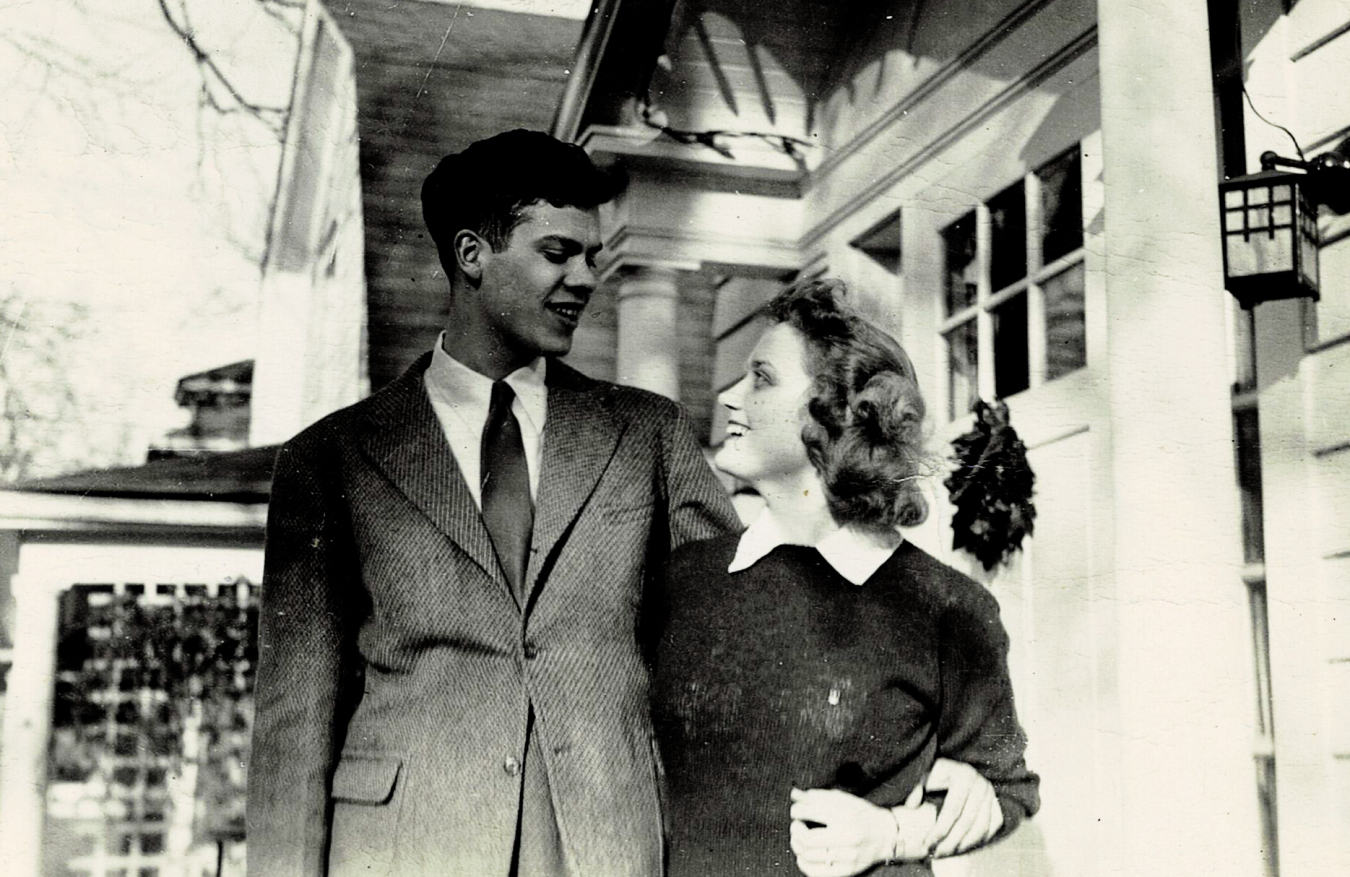

Ethel Fischer was at the Metallurgical Laboratory.

Fischer — a freshly graduated chemistry major in need of a job to support her newly formed family — worked at the Metallurgical Laboratory for two years. As Fischer celebrated her 100th birthday in 2023, she recollected her work with pride.

“My husband and I got married [in 1942] on a Friday in St. Louis, and we just had the weekend together,” Fischer recalled. “On Sunday we went back to Chicago where he was in school. He had to report at the Navy pier to be installed on Monday, and that same day I went to the university to look for a job.”

Scientists from across the United States coordinated efforts to develop and design the first nuclear weapon. For the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago, this work famously included designing the world’s first experimental nuclear reactor and creating the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, but scientists also worked on a variety of other projects without fully understanding how or why their work was so important.

“I knew no matter the task, I could do it, no question in my mind,” said Fischer, who said she was unaware of the impact of the work at the time, but later came to understand the magnitude of what happened at that unassuming location.

Starting in 1942, Fischer had several roles in the top-secret project. She described an ongoing, underlying current of urgency in her work, but said that no one spoke of it explicitly.

“There was anxiety of the race against time,” Fischer said. “It was just part of our lives at that time, as were the scientists.”

At first, she spent time doing minor experiments and researching while project personnel organized departments and constructed buildings. Her first official role involved work with a cyclotron — a type of particle accelerator — cleaning, maintaining, and monitoring the equipment. She did this work in the Service Building, which she described as a small shed. She was required to wear a dosimeter, a device to monitor radiation exposure.

“It was so hot working in that shed,” Fischer said. “There were no windows or AC in the building at that time. A coworker would bring me iced tea in the afternoons because it was so hot.”

Her most memorable role was performing autopsies on irradiated animals, such as rabbits and chickens. She took samples for testing to determine the effects of radiation on living beings.

She would complete the procedures first thing in the morning, then compose and study the slide samples under a microscope in the afternoon, along with other assigned scientists.

“It was not uncommon for scientists to work around the clock,” she said. “They were completely devoted to the project, and it demanded the majority of their time.”

Not only was the work itself memorable, but she was able to work alongside two of her closest friends. They referred to themselves as the Three Musketeers, and she remained friends with one of the women for 70 years, until Fischer’s friend passed.

Fischer’s later duties on the project were with the transportation department. Scientists needed ways to safely get to and from different sites, which required tact and planning due to the impact of World War II. Factors including strict gas rationing, limited production of vehicles, and limited access to rubber for spare tires created challenging transportation problems.

Her role involved arranging transportation for the scientists and coordinating gasoline rations. She even recalled riding in a vehicle with J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos National Laboratory, several times.

Fischer remembers the moment she heard the news that scientists had successfully created a self-sustaining reaction — a critical element in developing a nuclear weapon, and the first major technical achievement for the Manhattan Project. She was in her office when her supervisor called her and informed her of the event. The weight of that news left her almost speechless.

In that moment, she could only respond, “Oh, that’s nice.” At the time, she knew this was a significant event, but had no idea of the true implications of this breakthrough.

This would not be the last time she would feel complex emotions about the project’s results.

After leaving work to focus on her family, she would learn of the first bomb dropping while watching the news. The emotions she described feeling were of great sadness and tragedy, but strangely also relief that the Allies finished the project first.

She worked on the project for a short time, in the span of her life. Starting and finishing her work as a young woman, she has since devoted her life to her family. Her first child was born the day World War II ended, with four others to follow. She is now a proud grandmother and great-grandmother. She has had the opportunity to care for her husband and find her passions: quilting, gardening, baking, and community service, among other interests.

She celebrated her 100th birthday in September with her large family and a host of guests at her daughter’s house — a genuine celebration with the people she cares for most. She has made the cakes for weddings and big events of her family members throughout the years, and insisted on making her own cakes for the party — all seven of them.

“The most important thing in life is not the things, but the people. And that’s it,” she said.

History at the Chicago South site did not end with the Manhattan Project.

The reactor at the University of Chicago was disassembled and transported to a more remote location in a forest preserve outside Chicago. This location is managed as part of LM’s Site A/Plot M, Illinois, Decommissioned Reactor Site.

The Chicago South site was decontaminated in the 1950s using state-of-the-art techniques for that time. In 1977, as part of a facilities renovation program, the University of Chicago decontaminated Kent Chemical Laboratory, including removing contaminated sewers and some soil beneath the building.

The site was further remediated under the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program beginning in 1984. FUSRAP was established in 1974 to remediate sites where radioactive contamination remained from the Manhattan Project and early U.S. Atomic Energy Commission operations. FUSRAP remediation included portions of Kent Chemical Laboratory, Jones Chemical Laboratory, Ryerson Physical Laboratory, and Eckhart Hall. Remediation of the Chicago South site was completed in 1987.

In 2004, DOE transferred long-term stewardship responsibilities for the Chicago South FUSRAP site from the DOE Office of Environmental Management to LM.

As of today, no monitoring, maintenance, or site inspections are needed for the Chicago South site. LM manages site records and responds to stakeholder inquiries.